A group of passionate Native Americans assembled to protect the history of their culture said they support the use of Sachem and Flaming Arrows names used by the Long Island school community.

The Native American Guardian’s Association (NAGA) is a non-profit organization advocating for increased education about Native Americans, especially in public educational institutions, and they find honor in using Sachem as a district name, the Flaming Arrow moniker, and its use as a logo.

“We’re offended a state such as New York – which features Native American names and images on city flags and even in the logo, mayor’s office, police badges, and flags of NYC – would attempt to finish us off culturally by passing such damaging and offensive legislation,” said Eunice Davidson, the founding president of NAGA, a full-blood Dakota Sioux and member of the Spirit Lake Tribe from North Dakota. “It’s an honor to say you want to use a symbol that connects to our culture. It’s all in respect. It’s just a name and a symbol that recognizes our people. You guys respect it; you use it with honor to honor us.”

Through its Board of Regents, the New York State Department of Education voted on April 18 to ban the use of Native American names, logos, and images in 55 school districts, including Sachem. As part of the mandate, voted on unanimously and without an appeal process, school districts had until May 3 to gain approval from federally funded Native American tribes to keep their names and logos. If a district opts not to comply, they could lose state aid, or district officials could lose their jobs.

NAGA won’t be able to save the Flaming Arrow name, however. They weren’t hand-picked to the advisory council representing the Board of Regents in this standoff. And by standoff, a one-sided delivery of mandates that threaten school district funding and the livelihood of educational administrators. School district administrators and board officials hesitate to speak out in most districts out of fear for their jobs and school funding. Doesn’t sound very democratic. For instance, Sachem’s administrators and board have not issued a public statement on the ban since it was delivered.

There are two sides to this story: what New York State wants you to hear and what would have been a more thoughtful process that included all stakeholders, including Native Americans who want to preserve their history and community members who want to uphold those same values.

According to the state, it’s okay for their hand-chosen Native Americans to have a say in this backward process, just not other groups of Native Americans who believe in protecting their history, and certainly not community members and taxpayers from each school district. Even if they were open to it, the arbitrary deadline has passed, they say.

“Can you imagine what our ancestors would think if they heard of these few Indians standing with non-Indains?” Davidson said. “They are not warriors. They want to take the image and history away.”

The Board of Regents is standing on the “Dignity for All Students” Act to measure why the ban was instituted, suggesting that Native American students in public schools are uncomfortable with their heritage being used.

“We feel excited for our children that they won’t be exposed to stereotypes at the schools,” one Shinnecock Tribe representative told Newsday.

Davidson disagrees: “If we on reservations thought our names and images would hurt our youth, do you really believe we would use them for our own Indian schools for our athletic teams?”

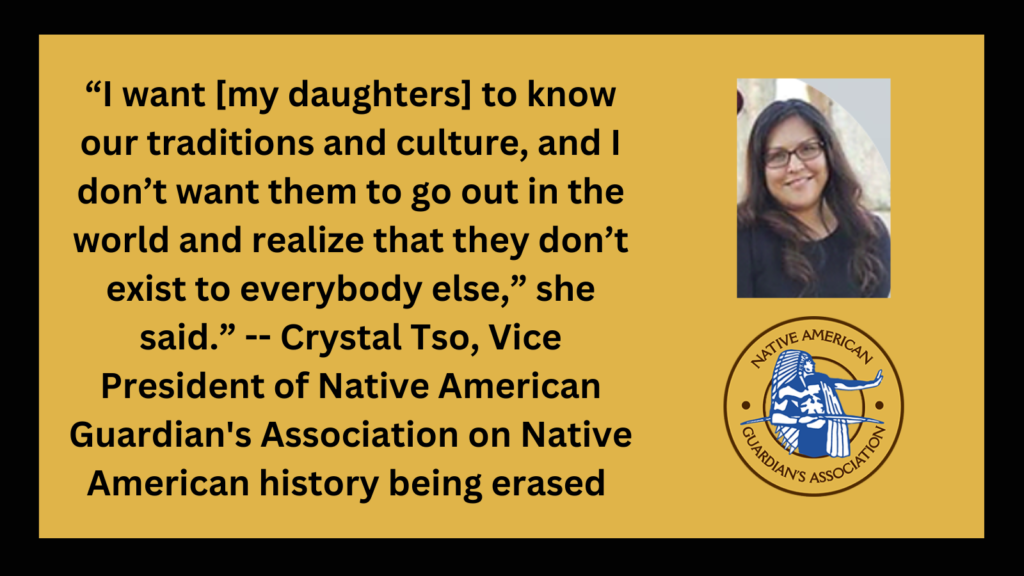

Crystal Tso, Vice President of NAGA and full-blooded Navajo from Arizona, helped found the 505 Redksins Fan Club to honor the now-defunct pro football team name. She hopes to instill Native American history in her daughters on their reservation.

“I want them to know our traditions and culture, and I don’t want them to go out in the world and realize that they don’t exist to everybody else,” she said.

In speaking with representatives from the NAGA, they were given an explanation of the meaning of Sachem’s name and how the moniker Flaming Arrows was developed shortly after the district was centralized in 1955, including that most of the district buildings are named after famous Native Americans and that Long Island has a deep and rich history of indigenous people. Their take?

“There’s nothing wrong with any of these names,” said Davidson, “and if you really think there were issues since 1960, you would have heard something.”

If this ban is pointed at public schools, shouldn’t the core issue be education? Shouldn’t one obvious measure be to update the curriculum at all grade levels and institute days of Native American dialogue and understanding in every district, especially ones close to reservations?

Education is one of the core values of NAGA. Their phrase is to “educate, not eradicate,” similar to the “embrace, not erase” message on Fox News during a measured request for open dialogue and inclusive communication with all stakeholders.

“That’s what we want to do, work with schools to educate and fill libraries with research,” said Davidson. “We’ll work with anyone that wants to work with us to educate their students about Native American history.”

NAGA has compiled endless research on keeping Native culture. You might find their documents and information on political corruption or their historical context timeline from 1860 to today interesting. Davidson also helped found NAGA as a method of advocacy for Native Americans looking for an outlet to preserve their identity but cannot speak out as individuals. Their organization serves as guardians of history and people.

“People who live on reservations are afraid to speak out because they feel they will lose something from tribal leaders,” she said. “Still, the majority of Native Americans that we get in contact with do not want these images to disappear.”

By chipping away at Native American history one community at a time, Davidson said it’s slowly erasing her ancestors.

“I’m fearful this is going to cause more genocide to our culture,” she said. “If that happens, we will become a forgotten people. This is our country, our home, and if it’s lost, we will disappear. The right thing to do is keep us relevant right now with names and images.”

Chris R. Vaccaro, a proud Sachem alum, is the Publisher of The Sachem Report and President/Founder of the Sachem Alumni Association, which works to honor the past and inspire the future of his community.